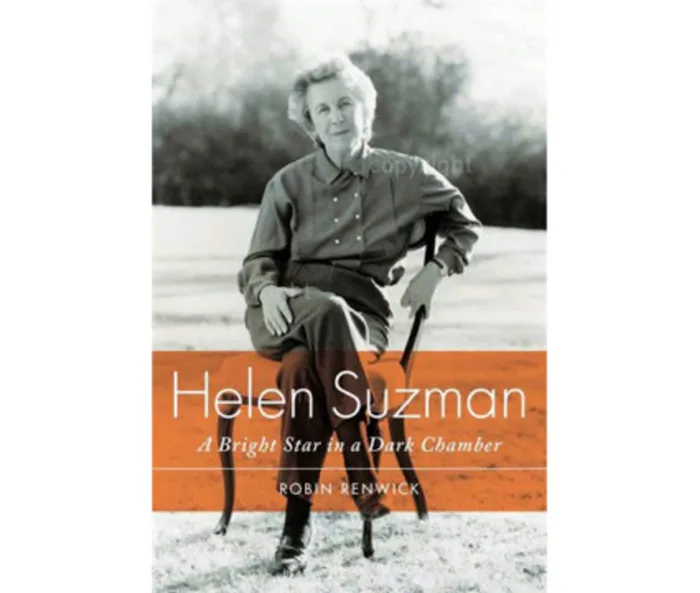

Review: Helen Suzman: Bright Star in a Dark Chamber

by Robin Renwick (Jonathan Ball Publishers)

Helen Suzman’s small stature gave the lie to the size of her personality – it was always wise to remember that she was far more Doberman pinscher than Yorkshire terrier. I saw her once, in 1986, storm out of a shack near Paarl to scold a sergeant in charge of 30 armed soldiers, all of whom were pointing rifles straight at us. They soon slunk away, shoulders and guns drooping. I almost felt sorry for them.

It is easy and perhaps convenient, in the hurly-burly of current, occasionally sordid, political events to forget the courage and integrity she displayed during her more than three decades in a Parliament deeply hostile to her presence, and the astute way in which she used parliamentary privilege to broadcast the darker doings of apartheid to the press and the world.

Were it not for her, for at least 13 lone years the sole anti-apartheid voice in the House, and the way in which she insisted in seeing the facts “with her own eyes” including the prison conditions on Robben Island and elsewhere, and then exposing them, the world may have assumed that all white South Africans supported human rights violations.

When Robin Renwick arrived here as the British ambassador in the mid-1980s, those of us who met him realised he was a very different brand of diplomat to his immediate predecessors.

Now Lord Renwick of Clifton (a life peer), Renwick was shrewd and pragmatic, a quick judge of character with the diplomatic skills to effect change behind the scenes (his later appointment to the premier diplomatic posting of Washington would confirm his judgement). Helen Suzman captured his interest and later, his friendship, for her authenticity and her principles, revealed in the opening quote of this book, “Like everybody else, I long to be loved. But I am not prepared to make any concessions whatsoever.”

It was one of her many friends and admirers, Chief Albert Luthuli (president of the ANC and South Africa’s first Nobel Prize winner) who in 1963 wrote to her: “For ever remember, you are a bright Star in a dark Chamber, where lights of liberty of what is left, are going out one by one.”

Suzman first met Nelson Mandela on Robben Island, when he stuck his hand out to her from behind his bars; he would remember later that it was an odd and wonderful sight to see this courageous woman peering into their cells. They became increasingly close, and she also befriended his then-wife, Winnie.

African statesmen lined up to praise and greet her, though not Robert Mugabe, whom Mandela also disliked, and whose dislike of Suzman she regarded as a badge of honour.

International honours poured in, too, including an honorary knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II.

Opposed to the death penalty, Suzman worked for the commuting of Robert McBride’s death sentence (for the bombing of Magoo’s Bar in Durban on June 14, 1986, in which three white women died and 69 people were injured), one of the slightly more startling facts in this short but valuable tribute.

There are few snippets about her private life in here. Renwick has chosen to be discreet on several matters, not least the rage she felt towards former DA leader Tony Leon over the manner in which he arranged his grab of her safe seat of Houghton (the blow-by-blow details of which she, seething, unleashed on me during a three-hour flight from Lusaka to Johannesburg in 1989).

After her portrait was displayed in the parliamentary corridor she received a congratulatory note from the then-Speaker, Louis le Grange, with whom she had long had a slightly flirtatious yet fierce sparring relationship – he joked that he had always wanted to see her “hanged in Parliament”. It is no credit to those sitting in the House that her portrait is now consigned to the basement.

Renwick’s written portrait offers some redress, and rekindles the truth and scale of her life of service. One did not always agree with her; but there was no doubt, if you saw her at work, that she was a fizzling “star” in a very dark chamber. Luthuli’s description was spot-on.