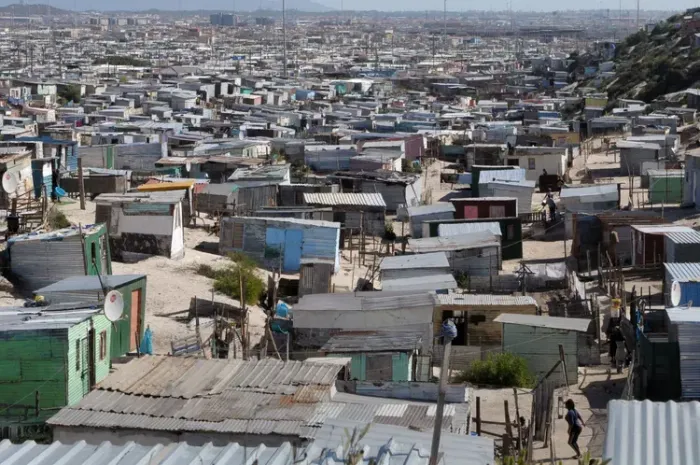

South Africa's Khayelitsha township in Cape Town.

Image: Tracey Adams/Independent Newspapers (Archive)

South Africa's public sector is often caught between two critical goals: achieving clean audits and delivering quality services to citizens. While both are essential pillars of good governance, the country has developed a troubling pattern of prioritising clean audits — often hailed as signs of sound financial management — while service delivery on the ground continues to deteriorate. This false dichotomy is not only misleading, but dangerous.

In the 2023/24 Auditor-General’s report, several municipalities were commended for receiving clean audits, suggesting improved financial controls and accountability. Yet, many of these same municipalities are failing to provide basic services such as water, electricity, refuse removal, and road maintenance. Clean audits, in their current interpretation, often become a checkbox exercise — a paper-thin façade of good governance masking the harsh realities of dysfunction and neglect experienced daily by communities.

A "clean audit" means a municipality's financial statements are free of material misstatements and comply with accounting standards. It indicates good record-keeping, transparency, and adherence to rules. While these are crucial attributes for any institution entrusted with public funds, they are not synonymous with effective governance. A clean audit does not mean that money was spent wisely, or that communities received value for their tax contributions. It merely means that money was accounted for properly — even if it was used ineffectively.

Consider the glaring contradiction in places like the Western Cape’s Stellenbosch Municipality, which has often received clean audits while its informal settlements still struggle with access to clean water and sanitation. Or contrast the audit outcomes of many rural municipalities in the Eastern Cape, which may have improved technically, yet continue to experience rampant potholes, broken infrastructure, and failing clinics. This mismatch between administrative compliance and lived reality reveals a deeper crisis: a governance culture more focused on impressing auditors than serving people.

This is not to suggest that clean audits are unimportant — far from it. Financial mismanagement and corruption have devastated many parts of the country. In fact, South Africa desperately needs tighter financial controls to rebuild trust in public institutions. But when clean audits become the ultimate goal, rather than a means to an end, we risk incentivising bureaucratic box-ticking over transformative governance.

The obsession with audit outcomes can also lead to perverse incentives. Officials might delay or avoid critical expenditures — such as infrastructure maintenance — out of fear of making audit errors. This results in underspending on capital projects, especially in poorer municipalities that are in dire need of basic infrastructure. In 2022 alone, the National Treasury reported that municipalities had underspent billions of rands in conditional grants meant for water, sanitation, and housing. In many of these cases, the priority was not to spend effectively, but to avoid audit findings.So, how do we shift the narrative?

Firstly, we must redefine success in public governance. Clean audits should be one of many indicators — not the only one. Municipal performance assessments should also measure service delivery outcomes, citizen satisfaction, infrastructure functionality, and responsiveness to community needs. A municipality that delivers clean water, reliable electricity, and functional roads, even with a few audit findings, is arguably serving its people better than one with a spotless financial report and crumbling infrastructure.

Secondly, we need to build capacity at the local government level. Many audit failures stem not from corruption, but from skills shortages and poor systems. The national government must invest in training, mentoring, and support for local officials to build a competent, ethical public service that can both deliver services and comply with audit standards.

Lastly, communities must demand more than clean audits. Public participation in municipal planning and budgeting processes must be strengthened. Citizens must be empowered to hold officials accountable for both financial integrity and real-world results. A clean audit is of little comfort when a community’s taps run dry or its streets remain unlit and unsafe. South Africa cannot afford to choose between clean audits and service delivery. We must pursue both with equal vigour, recognising that true accountability lies not only in books that balance, but in lives that improve. Only then will we move from a governance system that looks good on paper to one that truly serves its people.

*Mayalo is an independent writer and the views expressed here are not necessarily those of IOL or Independent Media