Without consensus, SA is lost

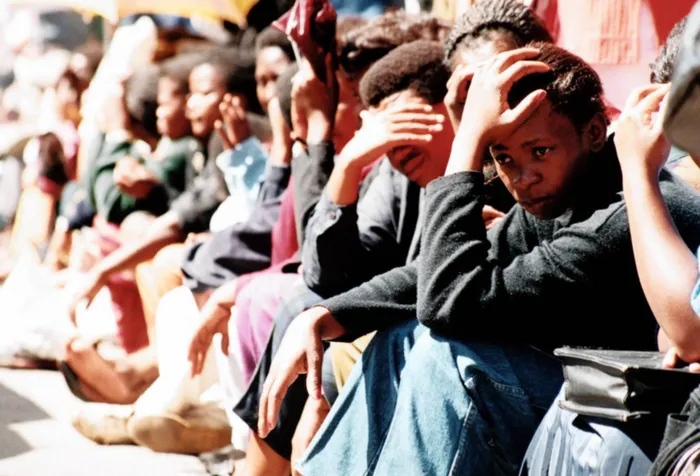

NO JOBS: Approximately 25 percent of the country's workforce is unemployed. Worse, 72 percent are between the ages of 15 and 34. SA is facing a crisis of epic proportion, and there seems to be no consensus on how to deal with it, argues the writer. NO JOBS: Approximately 25 percent of the country's workforce is unemployed. Worse, 72 percent are between the ages of 15 and 34. SA is facing a crisis of epic proportion, and there seems to be no consensus on how to deal with it, argues the writer.

‘Why would the government want to tax us more when they can’t even spend the revenue currently at their disposal?” asked one corporate executive.

The question came up in the midst of a discussion on the ANC’s proposal that taxation of the mining industry be increased to a maximum of 50 percent of its profit.

The drafters of the proposal consider it unfair that private individuals should be sole beneficiaries of immense profits from products that are otherwise collectively owned. This is a legitimate point, but it still doesn’t nullify the fact that the state lacks the capacity to spend.

Provincial governments return funds to the Treasury. They do so not because there isn’t any need upon which to spend them. The needs are plenty and dire. Provincial governments simply lack the skills, and even interest in some cases, to spend their budgetary allocation.

Consider the recent burning of a school, a structure that looked as if it was made of cardboard, by students in the Eastern Cape. The students simply got fed up with going along with the charade of a school. Their situation was no different to learning under a tree. So they got rid of the façade.

Yet the province is unable to spend its budgetary allocation. So the question is indeed legitimate: why seek more revenue when you can’t even spend your current revenue collection?

I suppose the ANC’s proposal and the protest against more taxation are both correct, at least partially. If indeed the state is the legitimate owner of the minerals, then the argument that it should not share in their profits is difficult to sustain.

Conversely, the profits may be better left with business, where they are likely to be reinvested back into the economy, than in the coffers of a government incapable of spending them. The crux of the problem is the absence of a social compact.

Just as business believes the public sector is wasteful, so the government is convinced that business people are self-indulgent. And workers always remind us of the obscene salaries earned by their bosses while they go home with pittances.

The government has repeatedly complained of an investment strike by local business. Business and government seem poles apart. And now business even lacks a singular voice. The racial fissures have re-surfaced. Part of black business has broken away from the largely multiracial Business Unity SA (Busa) to reconstitute itself as a predominantly black body, the Black Business Council.

No less than four ministers attended its launch, professing support for growing black business. I wonder how many people Busa will be able to attract to future functions. But Busa members own the bulk of private capital, and ultimately the government needs their commitment to grow the economy.

SA is not without precedent in a partnership between the public and private sectors. Historically, our economy was spurred by a social compact involving government, business and (white) labour. Black labourers were left out of the pact and subjected to exploitation.

Successive governments over much of the 20th century supported business not only to promote national development, but also to create employment in order to eliminate the “poor-white problem”. State-owned enterprises sprung up, while white business got cheap black labour and financial aid. That’s how apartheid SA managed to become the biggest economy in Africa.

That history offers instructive lessons for today.

Firstly, the National Party, white labour and white business shared a common ideology. They were tied to each other by Afrikaner nationalism. SA belonged to the Afrikaner volk. And each component had a duty towards the success of the volk.

Secondly, concerted efforts towards national development were triggered by crises like World War II and growing isolation. A platform arose for the growth of self-sufficiency. Afrikaner nationalists grew determined to show the world that they could do it all on their own.

Present-day SA faces its own grave crisis, but lacks a consensus on a solution. About 25 percent of the country’s able-bodied population is unemployed. More worrying is that 72 percent of these unemployed fall between the ages of 15 and 34.

Of this cohort, 82 percent did not go beyond Grade 12 at school and 66 percent have never held down a job. They face a bleak future, and they know it.

This is what makes them bitter, and it is that bitterness that could explode into social upheaval.

It’s easy to strike out against society when you don’t have a stake in it and feel neglected.

The spectre of social upheaval, however, has not yet cultivated a consensus in SA’s economic plans.

The Treasury has suggested a subsidy for youth employment. But labour has dismissed the idea as an attempt at creating a dual labour market, and fears it would weaken its organised power.

In turn, the Treasury sees the labour regime as unattractive to investors.

SA is in the grip of an impasse. And our national demeanour belies the catastrophe that may be spawned by these social ills. Perhaps we need an outsider to trigger a meaningful conversation on the subject. MISTRA has invited one of Africa’s finest social scientists, Thandika Mkandawire, to give a lecture on the subject at Wits University at 6.30pm tomorrow.

l Mcebisi Ndletyana is head of the Political Economy Faculty at the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (MISTRA).